In Parts 1&2 about my great- grandmother Amalya, I was able to pay tribute to the tragic loss of life in her family. These were very difficult, painful posts to write; they were not polished or literary; i just wanted my family members’ lives and stories to be remembered and honoured and to be accessible online. For various reasons, it took me several months to have the courage to take up my iPad again and continue to tell the story. ( There have meanwhile been many changes to the WordPress blog forum, rather confusing for me, but i think I managed to record the desired content!)

Now I want to write about some of the heroism in my family, and in particular, about Amalya’s grand- daughters, four cousins, four young women, aged 15, 16, 18 and 20, who, along with their parents’ encouragement, ensured that there are descendants of Nathan and Amalya Aszkanazy living today!

This year, I have had the immense and unexpected privilege of “meeting” and speaking via media with a cousin on the westcoast of USA, having a first time email exchange with another cousin whose family lives on the east coast of the USA, and have continued some correspondence with cousins in Europe and Israel. These cousins have children and some have grandchildren, so the family line and stories continue!

All these cousins (whom I will not name for privacy reasons), along with myself and my two brothers, have the same great- grandmother, Amalya Malka Meisses Ashkenazy! Until two years ago, our generation did not even know that we had each other….cousins from this branch of the family!!

Deep gratitude goes again to my niece Kathy Simpkins who tirelessly researched my grandfather Szymon Aszkanaszy’s family – following up a couple of small clues gleaned from my Granny’s memoir, and also to Yad Vashem for their constantly expanding data- base records and to my newly found cousins, who either in person, or through email, kindly shared with me stories and photos from their precious memories and photo collections.

Our grandfather Szymon was an older brother ( by 12 years) to their grandmother Roszalia, the youngest child of the five: Nachim, Szymon, Paula, Joszef, Roszalia.

Our mother Lore, and out Aunt Lisl were therefore, first cousins to their mothers, Martha and Elizza.

Apparently, the four girl teenage cousins knew and visited each other during their childhood and teen years in Wien, until the shocking end of their way of life on March 12, 1938, when Nazi troops marched into Vienna.

Martha ( Mausy) and Elizza ( Litsa) and their parents, Roszalia and Max.

Martha and Elizza visiting their Grandmother, Amalya in Sanok, Galicia, Poland. Apparently, they visited the Sanok family regularly in the summers.

Amalya with Joszef, her third son, and wife, who ran the family hotel in Sanok, Roszalia’s family and other local relatives.

Amalya with Joszef, her third son, and wife, who ran the family hotel in Sanok, Roszalia’s family and other local relatives.

Meanwhile, my grandparents, Simon and Anna had bought and renovated a country home in a small town, Altenmarkt an der Triesting, in 1923.

Anna and Simon had really suffered, along with much of Europe, from the famine at the end of WW1. (Anna had actually survived Spanish flu that same year, 1918, when they lived in Budapest, while she was a newly wed, and became pregnant only a few months later).

After they fled from Horthy’s regime in Hungary and slowly became established in Vienna, they wanted to have a country home where they could grow fruit and vegetables and raise chickens and goats in case of another famine. My Granny Anna was an active eco- feminist, so this also made sense.

They were very aware that the next war would likely be fought, not in trenches, but from the air, and they wanted their family to have a safe place to flee to, away from the city of Vienna (a more likely bombing target), where they lived in an apartment.

Simon and Anna with daughters, Lisl and Lore, and Harry the dog. Altenmarkt, 1927.

Simon and Anna with daughters, Lisl and Lore, and Harry the dog. Altenmarkt, 1927.

The lives of these two families changed drastically on March 12, 1938, when Nazi troops marched into Vienna, the start of the Anschluss. Earlier that very day, Anna had been on the streets with fellow members of the Call Club, a women’s group that held lectures on political education and involvement. They were busy distributing pamphlets which encouraged a public referendum to be held on the question as to whether Austria should be annexed to The Reich. Only later that afternoon they heard that their Prime Minister Schusschnigg had already met with Hitler in “The Eagle’s Nest” and agreed to let him in; that evening the Nazis marched in. ( Hitler himself arrived two days later and on Monday 15th, held a huge rally in the Heldenplatz, in central Vienna, attended by 200,000 people.)

That Friday night, March 12th, Simon [“Wolf”] returned from business in Zurich at 11 PM. Anna and their two daughters met him at the train station, told him the frightening circumstances, and were ready to get right on the train then.

“But I just came back from there. I’m dead tired. Tonight those bandits have better things to do than to try and burglarize us. Let’s go home and sleep. Tomorrow we’ll decide what to do.”

So we drove home. I told the children they should sleep and at six in the morning we would decide what to do. Wolf and I couldn’t sleep, however. In desperation, we discussed the wildest plans. Wolf thought we should go to Altenmarkt first and await developments. I suggested Berlin because the Nazis would be concentrating on Austria, and we wouldn’t be noticed in Berlin. It was all crazy, but we couldn’t think straight anymore. Wolf said he wasn’t going to leave our home and all its art treasures to this rabble. I sat up and reminded him of what his friend, the Russian Professor Klitscheff had repeatedly told him in Belgrade about his own escape from the Bolsheviks and how he had had admonished Wolf to not allow himself to be distracted by his belongings when the subhuman scum flowed into Austria. “Whoever tried to save what he owned, perished,” Klitscheff had said.

Wolf nodded, but said, “That rabble will go after others first, and by the time they get around to us, we will be long gone.”

I was so terribly overtired that my head and my eyes hurt. Very quietly I said, “I’m afraid. These animals are mad. And the children: we can’t put the children in danger.”

He finally saw the light and gave in and agreed that we would leave in the morning. But where to? We couldn’t agree. He maintained again that we should go to Altenmarkt first.

We hadn’t slept a wink when at six a.m. the children came in.

“Where are we going” Lisl asked.

“Paps says we should go to Altenmarkt first.”

Lisl stamped her foot. “I don’t want to go to Altenmarkt, I want to go to Switzerland.”

“Me too,” Lori echoed.

“Okay,” I said. “If you want to go Switzerland that’s fine with me. We’ll go to Switzerland. The train leaves at eight o’clock. Pack your things. Take only what’s absolutely necessary. And get dressed now.”

Wolf went along with this. I called to the children and told them the authorities might not let us through the border, in which case we would have to cross the mountains on foot, so they shouldn’t pack more than they could carry. I took nothing but silly things: a few valuable handbags, but also even sillier things: I must have lost my senses and I didn’t even notice in my exhaustion that Wolf was not packing anything. His two small suitcases still stood there unopened from the night before.

Our old cook came. She had made coffee, but I have completely forgotten if we had breakfast or not. All I can remember is walking down the narrow corridor from the bedroom to the entrance hall. There I saw my brown pony fur wrap from Hartwich hanging on the hook. I looked at it and said, “What’s the use of carrying furs. It’ll be warm.”

Behind me I heard Lori half cry out in anger. She took the fur wrap from its hook and I took it along. And so I still have it!

Crazy Boleslav Kokoschka’s poor manuscript still lay on the table in the front hallway. I entrusted the cook to pass it on to the building manager and that I would write to that crazy Kokoschka that he could pick it up there. Then we went to the elevator. I still hoped that the manager’s family wouldn’t see us, but they were in the hallway sweeping on the way out, and I mumbled that we were going to our estate in Altenmarkt. Some taxis were nearby in Neulingstrasse when we got downstairs and we hailed them and the driver had to hoist our suitcases on the roof because there were four of us. It was very uncomfortable because everybody could see that we were leaving, fleeing.

But despite the fact that it was a work day morning—it was Saturday, seven- thirty—and despite the fact that our route took us all the way from the third to the sixth district where the Westbahnhof was, we saw almost no people in the streets. Vienna was as deserted now as it had been full of people the day before. We didn’t speak at all. We were dumbstruck, half dead from fear, exhaustion and shame. I felt as though I had personally lost the war. I had fought hard and now I had to take a humiliating retreat—from a band of crooks! They were mean, cowardly and disgusting, and for us all was lost. Had it not been for the children I think I would have killed myself. But if I had done that, I would have “taken one of them with me.” Who? Franz von Papen, of course. He was the meanest of the bunch.

When we arrived, the Westbahnhof was empty. We hardly saw any rail employees. Nobody was at the ticket booth. Wolf went to get tickets and came back and gave me three.

“Three?” I asked. “Where’s yours?”

“I’m not going to leave our household to those bandits. I’m not afraid. You go with the children, that’s the main thing. I’ll follow later with all our things.”

Speechless I stood there, my mind racing. “But we decided, all four of us….”

The children clung to him, but he said: “It’s late. You have to go. The train will leave any minute.”

I embraced him without a word and kissed him. He was unshaven and looked dishevelled, pale, sick. “Come with us,” I said in a barely audible voice.

“It’s okay, Mumilim. Have a safe journey.” And with that he led us to the carriage.

We boarded. Two ladies were in the compartment with us and when the train began to move we waved to Paps, who looked strangely small and shrunken standing there on the platform waving tiredly back at us.

When the train left the station I sat down and didn’t look out the window anymore. I was finished with Vienna.” – excerpt from Book 3.9 of memoir.

During the terrifying, 8-10 hour trainride on March 13, 1938, Lisl admonished her mother to smile and look cheerful, and to eat, so that they would not look like people fleeing! Anna wore some diamond jewelry: that was all they could bring out!

At a few stops, several Jews were violently pulled off the train. My family’s less stereotyped “Jewish features” probably helped to save them, as well as Lisl’s constant reminders!

They don’t exactly look like refugees, but here they are, actually three months after their flight from Vienna, in June, 1938 – when they came back to Switzerland briefly from London, England, to make sure their grandmother Malvine got out of Vienna). Granny also took the opportunity to call a WOWO meeting in Geneva- as the timing co-incided with the infamous Evian conference, where, of 32 western nations, all but the Dominican Republic refused to increase their quota of Jewish refugees – even in the face of the known impending tragedy. They sent Irene Harand to speak for them. Her pleas fell on deaf ears.

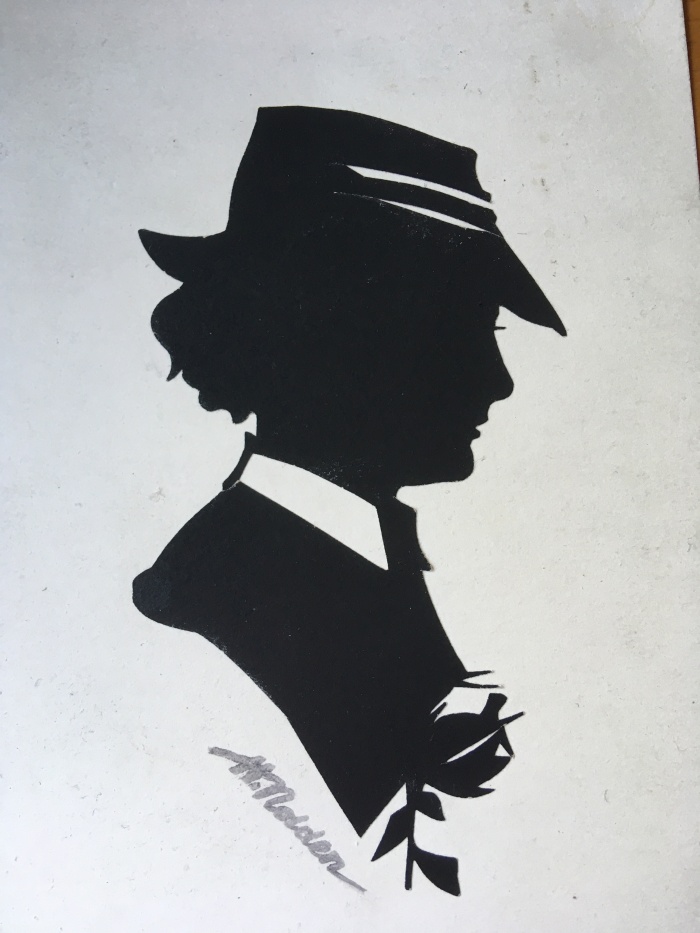

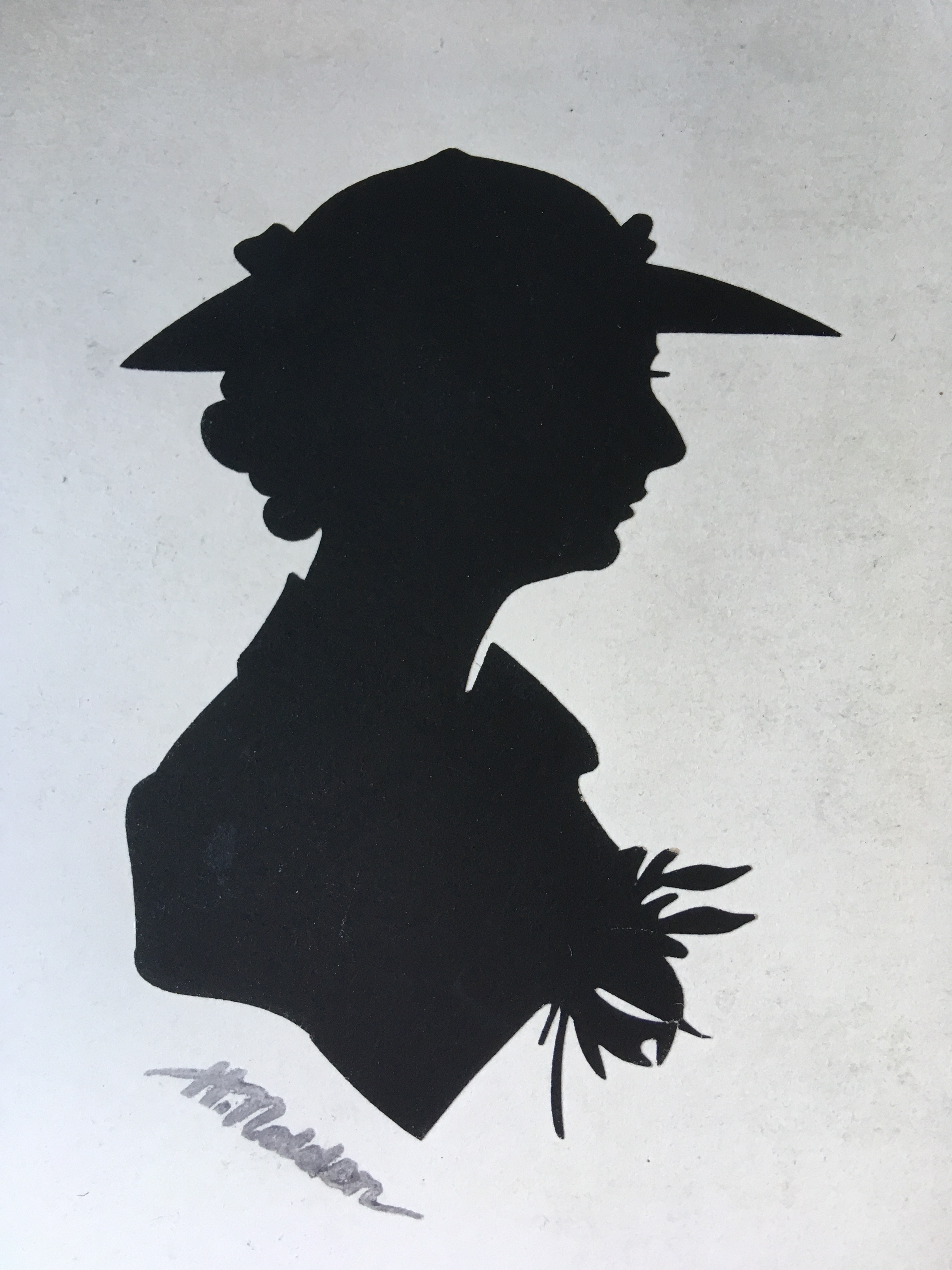

They stopped in Paris on their way to England, to help arrange a visa for one of Anna’s brothers. While there, they had their silhouettes painted and sent postcards to their grandmother Malvine Mahler, back in Vienna. Malvine, who initially responded to her sons’ encouragement to flee with : “Why should I leave Wien? I have done nothing wrong!” was later persuaded to flee to Switzerland as well, age 82, and was brought to Canada by her son Frederick in July 1939. She died in 1940, and is buried in Holy Blossom Memorial Garden in Scarborough, Ontario, close by the grave of her fourth son, Frederick Mahler ( d.1958), and as of 2017, they are joined by grand- daughter/ niece, Elizabeth Aszkanazy.

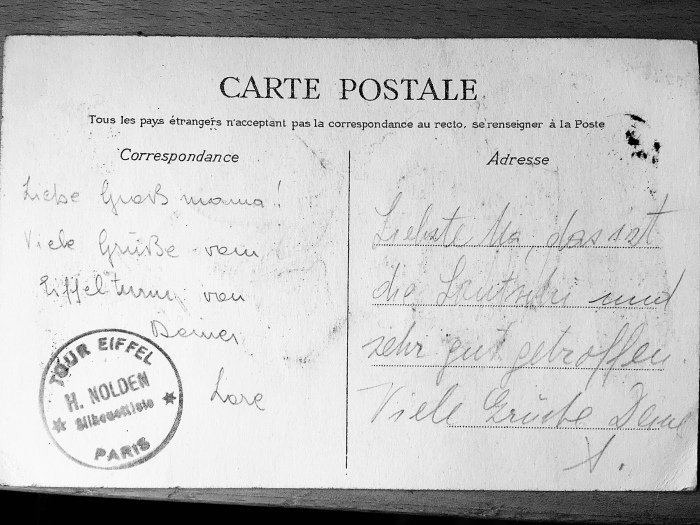

These tiny postcards were obviously precious to Malvine, and she saved them; they made their way into a photo album put together by my mother. Only a few months ago, I took these little photos out of the album and noticed that they were actually postcards with writing on the back – brief notes from Lisl, Lore and Anna to their “Grossmama” and “Ma” – on their flight to safety!

And now for some of the story of Roszalia’s family, as I recall from oral narrative and copy from email, by her grandson.

“Your grandfather Szymon Aszkenazy (also written Aschkenasi, Aszkenasi) was as you mentioned arrested and tortured to death by the Gestapo.

My grandfather, Markus Zuckerberg, was also arrested and detained for interrogation only my mother went to Gestapo headquarters and spent three days there demanding he be released. They actually let him go and my mother put him on a train to Zurich, leaving my mother, her sister Martha Josephine, and grandmother (Rozsia (Rosa) Zuckerberg (Aszkenazy) – Szymon’s younger sister — behind in Vienna.

The police came back a couple of days later, seized their passports, and said something like “Since you did such a good job of getting your father out, you can come and pick up your uncle.”

My grandmother was too frightened to go, so my mother went. They took her to the morgue and she told me that when she saw the condition Szymon’s body was in and the marks on his neck, she knew that they had strangled him. She buried him in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna. I have the row and number of his grave and will get it for you, unless you already have it.

She told me he made a fatal mistake by staying on to try to pack up his possessions and that his wife and daughters, Liese and Lori, had emigrated to Canada and were living in Vancouver but didn’t have any more information.

To answer your questions, Joseph was beaten to death by Ukrainians in Sanok according to information we got.Paula died from TB. My grandmother, mother and aunt went first to Germany because they didn’t need to have passports and they thought it would be safer. After the Kristalnacht, they went to the border and swam across Lake Constance at night but were arrested by a Swiss border patrol, imprisoned in Kreuzlingen for a week, then sent back to Germany and detained there, then released. After that, they went back to a different section on the border and crossed into Switzerland at night and managed to contact my grandfather in Zurich. He was able to get them a 24 hour transit visa, only they couldn’t leave because the German consulate refused to issue them a passport for 2 years. As soon as they got the passports, the Swiss ordered them to leave and they went to France, Spain and finally Lisbon where they were able to obtain a visa for the U.S.” ( from email)

One final very recent addition to this story of these true life events from my family: a large diamond from one of my Granny’s brooches, which travelled out of Vienna under the nose of the Nazis, was recently chosen by our son Timothy Roosma, a great- great grandson of Amalya Aszkanazy, to be reset beautifully into an engagement ring for his chosen life- partner, Erika DyNing ❣️ What happy and good news!!

I am so very thankful to these four grand- daughters of my great grandmother, Amalya Malka Meisses Ashkanaszy, for their recognition of danger, and for their courage and strength in choosing to leave all behind and escape from life- threatening circumstances.

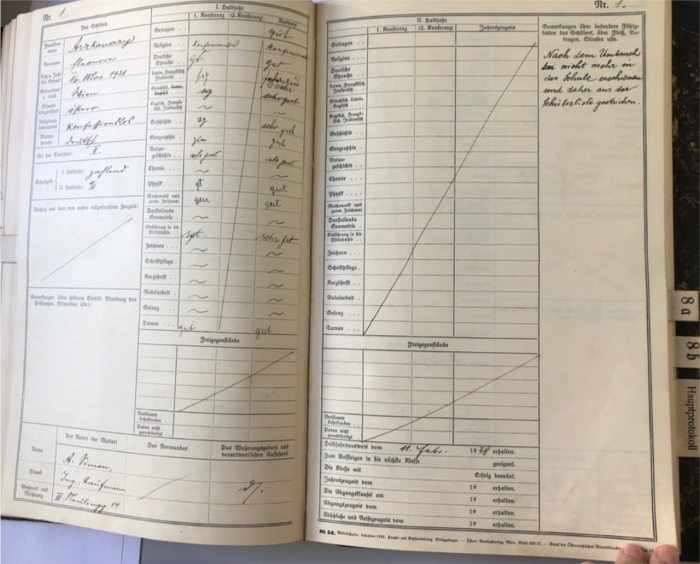

For Lisl, age 18, who stamped her foot and chose flight to Switzerland over staying in Austria; for her younger sister, our then 16 year old mother who said: “ Me too!”. The day before, Lore was a high- achieving highschool student at Kundmanngasse Gymnasium!

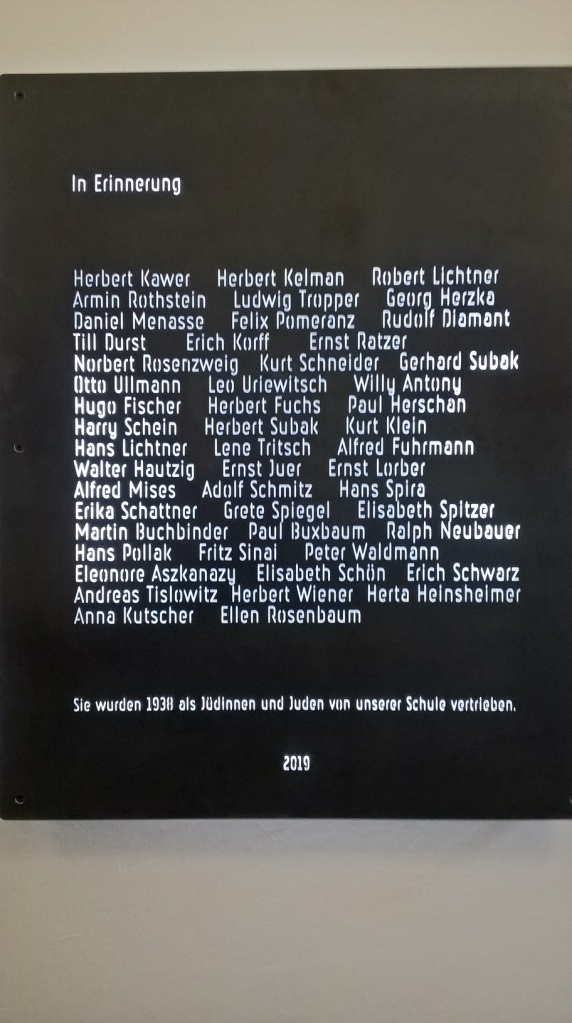

Last year, April 2019, that very school had a commemoration to all the Jewish children who fled or were expelled in the wake of the Anschluss. My mother’s school record ( below), which shows she did not return to school after March 12, 1938, was apparently the start of the project, initiated by a young history teacher, who found me and my brothers online ( yay Google!) and contacted us! Here’s a link to the commemoration event photos, and a link to an article about it in the Times of Israel. We also were sent hardcopy booklets, which featured a twopage article about my mother and her family, researched and written by a Grade 12 student at the school, Mary Yin.

Three new friends in Vienna, whom i met in 2018 when our family laid a memory stone by our family apartment, attended this event at the highschool. One sent me two hard copies of the booklet of articles written. The others kindly sent photos.

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1fn4tZUZQ8K4R0MBcoUFgedm-_narAbAX

I am so very thankful for the toughness of young Litsa Zuckerberg, who marched down to the Gestapo headquarters in Vienna, demanding her father’s release; for the swimming abilities of Roszalia, Martha and Elizza and their risk- taking and endurance in the face of life- threatening brutality and evil, to attempt escape again, and to succeed, with the help of kind people they met.

Of course, the trauma of these events left it’s mark in each survivor in a unique way; and some trauma has been passed on through the generations, again in a unique form, and it falls to each of us descendants to process in our chosen way.

Although there were some inevitable painful family disagreements and separations, I am so very thankful for the examples of family commitment to care for one another in their totally new surroundings.

I am so very thankful for my Granny Anna’s example to continue to help others with her time and money, once she arrived safely in Canada.

May Amalya’s descendants continue to choose life, and to be open-minded and of service to others.

This is a wonderfully moving piece. The transcribed section is so powerful. It took a lot of work to pull this together, and it was worth it. Mazel tov to Tim, Erika and your family. How touching to have the story behind that ring!

Glenda

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading Glenda….yes, Anna’s writing style and her personal story are compelling, and i am making plans to start publishing her long memoir ( English translation), a chapter at a time on an online forum. The German hard copy amd ebook publication was set to go in Vienna, May 2020….but with our present times, not certain now when that will actually happen! It’s time to be in touch with th editor and check in on his plans.

LikeLike