Below is Anna Helene Aszkanazy’s ( my maternal grandmother) speech, delivered in German at an international gathering in Geneva, September 1930, convened by the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and attended by members of the Human Rights League, the League of Nations and the Quakers ( Society of Friends).

First some background…..

In 1928, Anna had attended a conference of The Women’s League for Peace and Freedom in Prague. There she had heard Rosika Schwimmer speak on the rise of fascism in Europe.

Rosika was a Hungarian Jewish feminist peace activist who worked tirelessly for women’s rights and suffrage, and had fled Hungary for political reasons in 1920. She settled in the USA but was never given citizenship because of her outspoken pacifism!

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosika_Schwimmer

During a break, Anna summoned up her courage and asked Rosika Schwimmer what she could do to help with world issues; her children were now attending school and she had time and energy and the will to be involved. Rosika commanded her to “look after the stateless”, telling her it was a hidden, but huge issue even in Vienna itself.

The other woman at the 1928 conference who impressed my Granny was Agnes McPhail, a Canadian MP who spoke very eloquently.

“A Canadian, Agnes Macphail, was called to the podium and made a speech in English, which––to my happy surprise––I understood word for word. It was like a revelation for me. Macphail was between thirty and forty years old, pretty, tall, dressed in light brown silk that shone almost like gold. She was a Member of Parliament in Canada, and one of her achievements was that for every hundred dollars spent on armament, one dollar had to be devoted to peace propaganda, something that was wildly applauded by all the delegates. I liked Agnes Macphail very much. I wanted to speak like her––as loudly, clearly, fearlessly, and masterfully. I decided that as soon as I was back in Vienna, I would found a school for public speaking where I would learn the ABCs of oration because I finally had to get over being so ridiculously afraid whenever I had to speak.” ( from Anna’s memoirs).

Anna returned to Vienna and began to look into the matter of statelessness. It took her some time to find the right connections, and meanwhile she concentrated on learning to public speak, and did start a school in her home, beginning with 5 women and growing to 60 women, all meeting in their living room initially. Then they rented a hall, which my grandfather paid for, and the group continued to grow, ( according to my Mum’s stories I heard while growing up, to 200 women!)

Once Anna met Dr. Viktor Englander, a member of the League for Human Rights in. Vienna, she began to learn of the dire situation of the stateless in her own city, as well as neighbouring countries and began with a small team to work tirelessly at this enormous problem. She was encouraged by The Women’s League for Peace and Freedom to present the situation at a conference.

With her international connections, she gathered a team who worked hard and provided statistics, and by September 1930, she was able to present a coherent persuasive speech in Geneva, Switzerland, outlining the problem.

Simon and Anna with Lisl and Lore, and Harry the dog 🙂 and a photo of my Granny in 1931 on a pass for a writers’ conference.

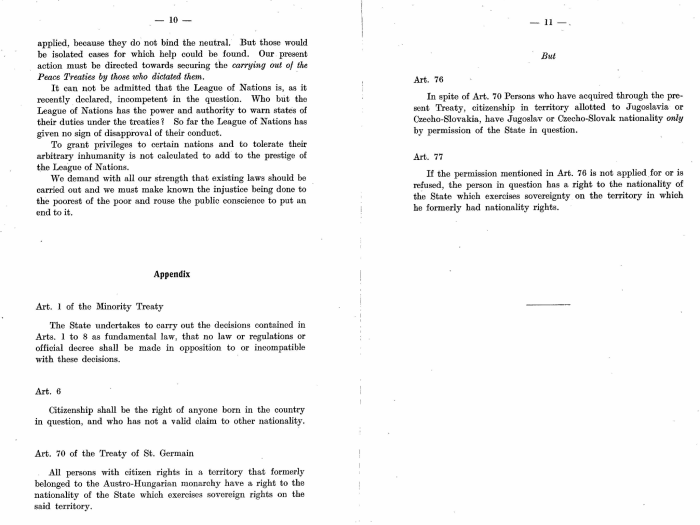

Here is the speech she gave ( just discovered in print and accessed from Harvard Archives by our translators this June!)

A big thank you to Anuschka Elkei and Uma Kumar, our translating team, for all your hard work! Only 10 more chapters – 300 pages – to go 🙂

Here is her own account of the experience and the results ( taken from her memoirs presently being translated into English – this chapter of Book 2.9, was just finished this week, and our family is reading it for the first time, so these excerpts are “hot off the press”!!

“Since I not only had to accuse the succession states, but also the Austrian Government, I had gone to Ballhausplatz and notified a senior official. I think it was the Sektionschef (Department Head) Dr. Karl Sobeck who received me, a refined, slim gentleman with a handsome, well- shaven, pale face. He had listened to me in silence, and finally, he answered: “You will not accomplish anything. You will stand as before a wall. But for heaven’s sake don’t let this discourage you. Try to do everything in your power to help these people; otherwise, we will all just lose faith in humanity. We need people like you––to give us solace.”

Those kind words gave me strength. I got started. In front of me, in the first row, sat an older very tall gentleman with gentle features, well shaven, bald, and wearing a monocle. I instinctively directed my words to him when I looked up from my paper. He had a “positive” face! I didn’t know who he was. I was interrupted by calls for me to “slow down!” Since I was reading in German, all the speakers of other languages were trying to follow. I then moderated my speed, tried to enunciate as clearly as possible, but as soon as I got carried away by the material, I went faster again, and once again shouts admonished me. But I felt I had a hold on the audience, and they followed my words with bated breath. I had spoken for about an hour and three-quarters, and when I had finished, continuous applause followed, surprising me very much. It was my first successful speech, and I wasn’t used to it yet.

Then the fellow from the first row stood up, gave a slight bow in my direction and said:“ I am Lord Cecil and I propose that that the speech [by] Madame Askanasy should be translated into English and French. It should be printed and distributed among all the members of the League of Nations.” He sat down amid renewed clapping, and a gentleman stood up who suggested that I should be subjected to an interrogation because, in his opinion, not all of my numbers were correct. I was not expecting any questioning, much less that the most distinguished international lawyers would lead it, but the material was so engrained in my head that I was quite glad to share more and more of the things that I hadn’t been able to include in the report. I replied pugnaciously: “My language skills do not suffice. Is there someone here who understands all three languages and can interpret for me?” A lawyer from Geneva came forward, sat next to me and quickly translated all the questions I didn’t understand, and also conveyed my answers in English and French. It worked perfectly.

They grilled me for a full two hours. Lawyers from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Poland, as well as from England and France threw all sorts of questions at me, which I seemed to be able to answer to their satisfaction because, when there were no more questions, the audience gave me a standing ovation. Lotte whispered to me: “This is the greatest event the Women’s League has ever organized. Congratulations! It’s a complete success.”

I replied that it would only be a success if they met my two main demands. I had not only presented them in the conclusion of my report, but also argued them again and again during the interrogation––namely, that Nansen passports be issued to refugees and the stateless from all countries, and second, that the stateless be allowed to obtain work permits in their host countries. She said that from what she had gathered from the audience members, the League of Nations would accept both my demands and attempt to pass them.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nansen_passport

In short: my demand for stateless passports went through, although not all countries would recognize them––Canada among others. But most South American countries did agree to accept the stateless passports, with the result that countless stateless people were able to emigrate there. However, my second demand for work permits did not pass as the worldwide unemployment crisis was beginning to reach such proportions in 1928 that most countries in the world could not even shelter their own citizens from it.”

Hello, this is an excellent summary of some of my maternal grandmother’s involvements- well done! Hiwever, i have noticed a few inaccuracies eg, Anna had 5 older brother (not 4) and her husband Simon was primarily an engineer; he joined a business later ( Brüder Mahler), but worked as an engineer in the company. And a few typos.

Is there some way I can contact the publisher to have these and others corrected?

My email address:

jenny_roosma@yahoo.ca

Thank you, Jennifer Roosma

LikeLike